How the children of Godmanchester received their schooling largely reflects the history of education in England. For centuries, education's primary role was not to teach but to fit children for their proper station in life'. Education favoured boys as the future role of girls was bringing up children and running a home, so formal schooling was considered inappropriate and unnecessary.

Before the dissolution of the monasteries in the reign of Henry VIII, it was usual for boys of the middling rank and upwards to be educated by a priest in the chantry of the parish church or for sons (and sometimes daughters) of elite families to have a private tutor. Purpose built schools came into existence during the later Tudor period often funded by a wealthy member of the town who had made a bequest in his will or by money from retained chantry funds for the purpose of re-founding a School. In Godmanchester we can be proud to have one such school in the very centre of our town.

The Queen Elizabeth School was built as a result of a bequest made by Richard Robins in 1558 in his will for a Free Grammar School to be endowed from money raised from the sale of a portion of his land. In 1561, at the request of the town, Queen Elizabeth I granted letters patent granting her name to the School. An inscription to this effect may be seen under the porch window: ELIZ. REG. HUJUS SCHOLAE FUNDATRIX (Queen Elizabeth founded this School).

Schooling for poor children was a luxury their families often struggled to afford; children from a very young age were needed to help out at home or in the family workplace. The concept that education should be available to all children regardless of their sex and social status is a relatively recent idea; however concern was shown for this lack of education by Christian and philanthropic organisations, resulting in provision of charity Schools and Sunday Schools (both Anglican and Nonconformist). Teaching was undertaken by a school master and monitors to cope with the large numbers of children needing education.

Monitors were older pupils who had already achieved a basic level of education and were trained to pass it on to younger children.

The Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (S.P.C.K.) was established in 1698 to build Schools and provide basic elementary education for both boys and girls. The SPCK was an Anglican organisation providing National Schools whose object was to instruct children 'in the Christian Religion according to the Church of England and to bring them to church'.

A pioneer of the monitorial system of education in the early years of the 19th century was Joseph Lancaster, a Quaker from Southwick who was sponsored to form the British and Foreign Schools Society for the Education of the Labouring and Manufacturing Classes of Society of Every Religious Persuasion or in short the British Schools.

The Anglican National Schools and the Non-Conformist British Schools became staunch rivals in building schools and teaching their own brand of Christianity. From 1833 both schools were supported by government grants as there were no schools provided by the State at this time.

For the rest of the century there was contention over religious control over schools. The 1870 Education Act resulted in the state formation of school boards with power to build and manage schools where the provision by the National and British schools was inadequate.

Not many people are aware that Godmanchester had both National and British Schools just a few yards from each other. Education for boys was provided by the Queen Elizabeth School, but it wasn't until 1809 that a School of Industry for Girls was established following a Borough meeting held at the Horseshoe Inn.

It was agreed it should be built in Old Court Hall where King John's Terrace now stands between the butcher's and the baker's shops on a plot of ground to the south of the ancient Court Hall which stood on the same site as Richardson's the bakers.

The schoolhouse comprised 2 rooms for infants and older girls from 8 to 13 years and accommodation for 2 mistresses. The floor appeared worthy of special note as it was made from wooden block tiles about 12 inches square forming a dry, warm flooring for the children's feet, and likewise admitting to their moving about without the usual noise'. The girls were taught reading (but not Writing) and plain sewing and knitting. In 1854 it was recorded that there were 30 - 40 children daily attending the Girls School under the mistress Matilda Porch and about 88 infants in the care of Mary Ann Webb.

By 1844 the Old Court Hall which was built in 1679 from stud and mud had deteriorated to the point where it was considered beyond repair. The Council resolved to Sell the building and use the proceeds to erect a new Court Hall and Station House on School Hill. The Girls' School of Industry had been run by a Board of Trustees led by the vicar of St Mary's Church and in 1867 it was sold at auction at the Bull Inn to Charles Lord a local builder for £300 to build St John's Terrace (now named King John's Terrace).

The following year it was agreed by the Charity Commissioners that the proceeds should go to the building of a new school on a different site. The new National School was designed by the architect Robert Hutchinson for a cost of £1200 and was renamed St Anne's School for Girls being built on a plot of land between St Ann's Lane and The Stiles. The town's boys of infant age beginning their schooling also attended here whilst the older boys continued to use the Queen Elizabeth Grammar School.

King John's Terrace built 1868 on the site of Girls School Of industry and the Old Court Hall

The new County Primary School was built in 1955 in Park Lane and the vacant St Anne's Girls' School was used by the De Silva Puppet Company before being demolished in the early 1980's. Woodley Court now stands on the site and all that remains of Hutchinson's school are the two semi-detached mistresses' houses at the left of the entrance into Woodley Court in St Ann's Lane.

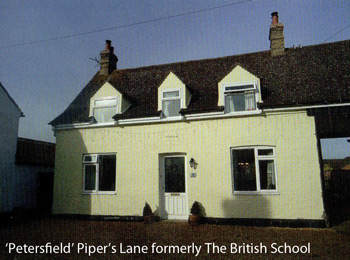

The British School in Godmanchester can be first traced to Piper's Lane in F. W. Bird's "Memorials of Godmanchester' (1911) where he remembers it was originally held in a large building in Piper's Lane which later became the Salvation Army Hall. Bird was born in 1837, the year that Queen Victoria came to the throne and he claimed his memory reached back to 1841.

It is not known exactly how long the British School used the large building in Piper's Lane, but Bird remembered a Mr Stuckey was the first master followed by a Mr T. Crafts. The British Schools' aim of educating the labouring and manufacturing classes from all denominations was very much carried out in Godmanchester.

It had a large attendance of both boys and girls many of whom according to Bird, came from the large families living in Adelaide Terrace built to house the employees of the Oil Cake Mill in the mid-19th century and situated on the Godmanchester bank of the river. It stood along the main road in front of the mill (now the Riverside Mill flats) and where the car park now stands.

In 1858 the Newcastle Commission was set up to examine schooling for the labouring classes on the understanding that it should be cheap, efficient and should not normally take children beyond the age of eleven'.

The Commission statistics given for attendance were encouraging however in reality many of the children on the register did not always attend as they were required to help at home or in some form of Work.

In 1858 Godmanchester was classed as an agricultural district and out of a population of approximately 2500, 75 children attended the British School (45 boys and 30 girls). There was 1 master and 1 mistress who was employed to teach Sewing, each girl being charged 1d a week.

A wide range of subjects was taught apart from the '3 R's'; Geography, English History, Drawing and Scripture History. The School's annual income was £52 which was £18 deficient of the £70 required and funding and had to be supplied by the treasurer, Mr Lancaster.

Perhaps as a result of the Newcastle Commission the following year in 1859 a committee was formed to build a new purpose built British School. Although a piece of 'garden ground' measuring about 32 perches was purchased in 1862 in Piper's Lane from Mr John Lancaster, a farmer, by the Trustees of the British School, Mr Lancaster died before a conveyance could be executed. Nevertheless the building went ahead and the premises were held in uninterrupted possession by the trustees from 1863 with no claim or objection being made. The names of some of the trustees Will be familiar today: Bateman Brown, John Topham Gadsby (farmer and cattle dealer), James Bester (grocer), Thomas Mayfield (thatcher), amongst others. Henry Fairy (corn merchant) made the declaration and it was subscribed by the trustees before Gerald Hunnybun, the Commissioner of Oaths.

Perhaps as a result of the Newcastle Commission the following year in 1859 a committee was formed to build a new purpose built British School. Although a piece of 'garden ground' measuring about 32 perches was purchased in 1862 in Piper's Lane from Mr John Lancaster, a farmer, by the Trustees of the British School, Mr Lancaster died before a conveyance could be executed. Nevertheless the building went ahead and the premises were held in uninterrupted possession by the trustees from 1863 with no claim or objection being made. The names of some of the trustees Will be familiar today: Bateman Brown, John Topham Gadsby (farmer and cattle dealer), James Bester (grocer), Thomas Mayfield (thatcher), amongst others. Henry Fairy (corn merchant) made the declaration and it was subscribed by the trustees before Gerald Hunnybun, the Commissioner of Oaths.

The British School continued to educate a section of the local children until 1887 when it came up for sale by auction at the Royal Oak Inn and was bought by James Isaac Tysoe of Godmanchester for £200. F.W. Bird surmised that "it ultimately collapsed for lack of funds as many of the principal supporters died off".

The deeds show a continuing life for the building after the demise of the British School. Today the school is a private house called 'Petersfield' but 3 years after the School closed in 1890 it was used as the Liberal Club. In 1906 it was bought at auction for £80 by James Higgins a baker who then sold it in 1926 for £150 to James Page the farmer who lived at Tudor Farm in Earning Street.

It was put up for sale again 4 months later and bought by William Yarnold a garage owner from Huntingdon for £130. Shortly after this purchase, Yarnold also bought the two little cottages next door for £65 from Florence Hunt, the widow of Samuel Hunt who had taught at the Oueen Elizabeth Grammar School.

In 1933 Petersfield was sold for £200 to Herbert Goggs a Chemist in a Huntingdon; after his death in 1946 the house and cottages were bought by Mr George Mayes a dairyman for £500. Ralph Clark told me that remains of the milking parlour may still be seen in Silver Street on the left just after the road passes over a little stream.

By Pam Sneath