The Roman town of Godmanchester, identified as Durovigutum, did not exist in isolation. Its creation was a result of the decision to invade Britain made a thousand miles away in Rome. Although we have no written accounts of the town's history in the Roman period, we can see the history in the archaeological record, and that events in Roman Britain and the wider Empire continued to affect the people

THE FIRST CENTURY AD

43AD Emperor Claudius invaded Britain. The fight against Rome was led by the rulers of the powerful south-eastern Catuvellauni tribe. The previous ruler, Cunobeline (Shakespeare's Cymbeline) enjoyed good relations with Rome, which heightened his wealth and power, displayed by the gold coins he minted from his capital at Camulodinum (Colchester). His sons, Caratacus and Togodumnus were defeated, Togodumnus died and Caratacus fled west to continue to fight Rome for the next nine years. Catuvellauni territory was rapidly subdued, in part by the construction of a series of forts.

One of these forts was built near a ford in the river Great Ouse to control the river crossing. There were already homesteads here, round houses of the local Catuvellauni people. The civilian settlement, or vicus, that grew up around the fort became the Roman town of Durovigutum, and later, Godmanchester. Remains of the early vicus have been found in Post Street and at Park Lane. With the south-east conquered, fighting moved out of the region, and the first fort here was dismantled before the ditches were completed.

60-61AD Rome attacked its ally, the Iceni tribe of what is now East Anglia. Their queen, Boudica, gathered a massive army and marched on the capital of the Roman province, Camulodinum (Colchester), then Londinium (London) and Verulamium (St Albans). On the way, the army attacked other Roman towns, and as we know Roman Godmanchester was burned at this time, it is likely that Godmanchester was attacked by Boudica's army. In the aftermath of the revolt, Roman Godmanchester was rebuilt along a regular plan, with land laid out in broad strips divided by ditches. A second, larger fort was constructed. One of its main gates was excavated in St Ann's Lane, and found to have a double carriageway flanked by timber towers. Its size suggests that it may have been a half-legionary fort.

THE SECOND CENTURY AD

By the early second century, the fort had been dismantled, ending the military phase of the town. But the civilian town continued to grow and flourish. This was partly because Godmanchester lay on Ermine Street, one of the most important roads in Roman Britain. It ran from London to York (Ebocarum). The line of the road running through the heart of Roman Godmanchester is still traced by the Stiles footpath and then south towards London by London Road. Initially the road in the town was twenty foot wide and surfaced with gravel extracted locally, but by the early second century it had grown to 43 foot wide and was more solidly built. Its repeated resurfacing during the Roman period is a testament to the heavy traffic coming through the town. Godmanchester's position in the road network connected it not only to the rest of Roman Britain, but to ideas and goods from the wider Roman Empire.

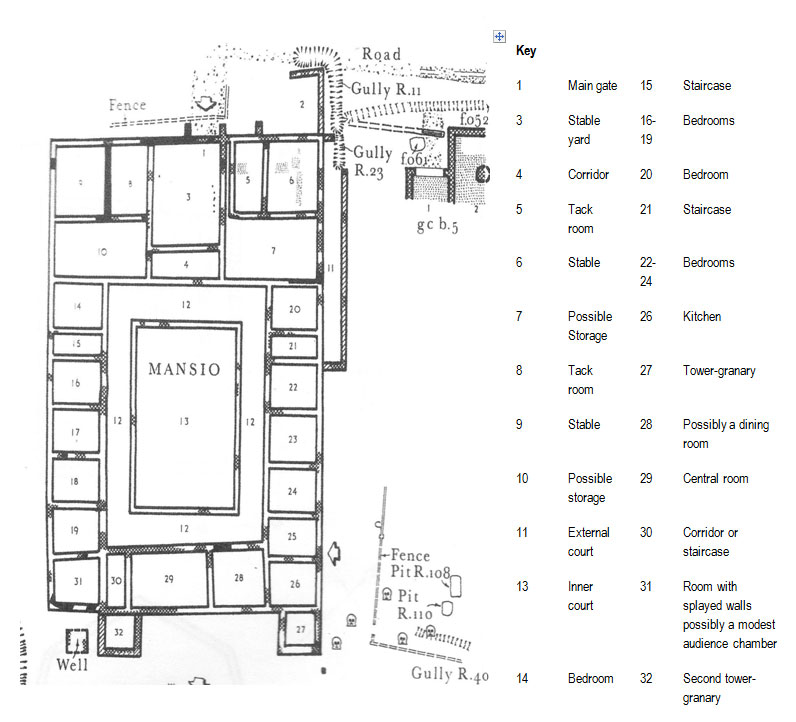

c120 AD The west side of the town was cleared, around what is now Pinfold Lane and Granary Close, and an inn for Roman officials, called a mansio, was constructed, along with a bathhouse and a temple to the local god Abandinus. It is the second largest mansio complex found in Britain, and its presence gave the town an official role in the communications network that was vital to the administration of the Roman Province of Britannia. Artists Impression

Artists Impression

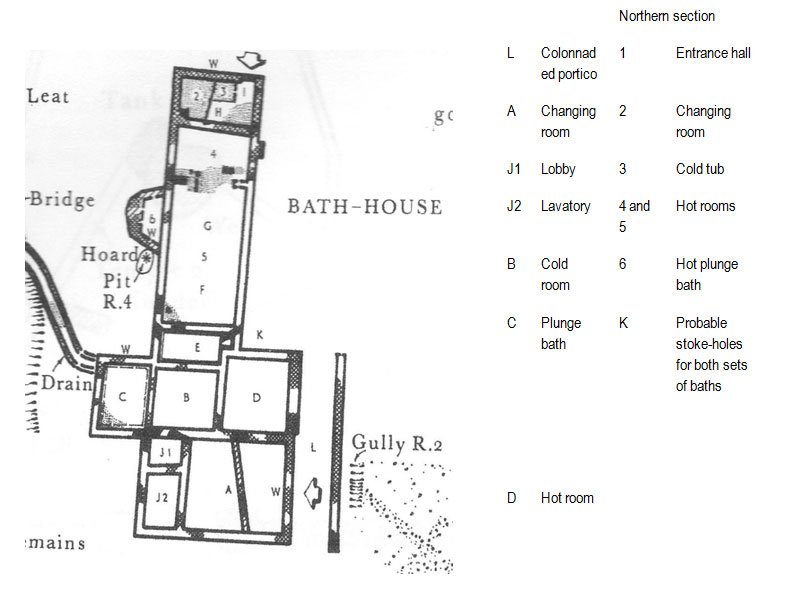

The bathhouse was part of the mansio complex, and constructed at the same time. Baths, with their series of cold, warm and hot rooms, were the heart of public life and stamped Roman culture on towns all over the Empire. Not simply somewhere to get clean, they were also places to socialise and do business. In Godmanchester, the organisation of the baths was altered during construction, resulting in two bathing systems in one structure. This was perhaps to separate male and female bathers, or for public and mansio use of the baths. The main entrance on the south side led to a large changing room, cold room (frigidarium), a smaller cold bath, a hot room (caldarium), and possibly a massage room (unctorium). On the north side a much smaller changing room led to a cold bath, and warm (tepidarium) and hot baths, possibly with a warm plunge pool. Remarkably, an impression of the boarded oak floor of the north changing room was discovered during excavation. The water for the baths was carried from Stonyhill brook by an aqueduct, and heated, possibly in metal cauldrons over the stoke holes of the furnaces. The warm and hot rooms were heated using a hypocaust system, where hot air circulated in a pillared space beneath the floor, then up through the walls via boxed flue-tiles. The rooms were decorated with mosaics, using both Celtic and Classical styles, and painted plaster adorned the walls. Fragments of glass show the bathhouse had glazed windows, allowing light in while retaining heat.

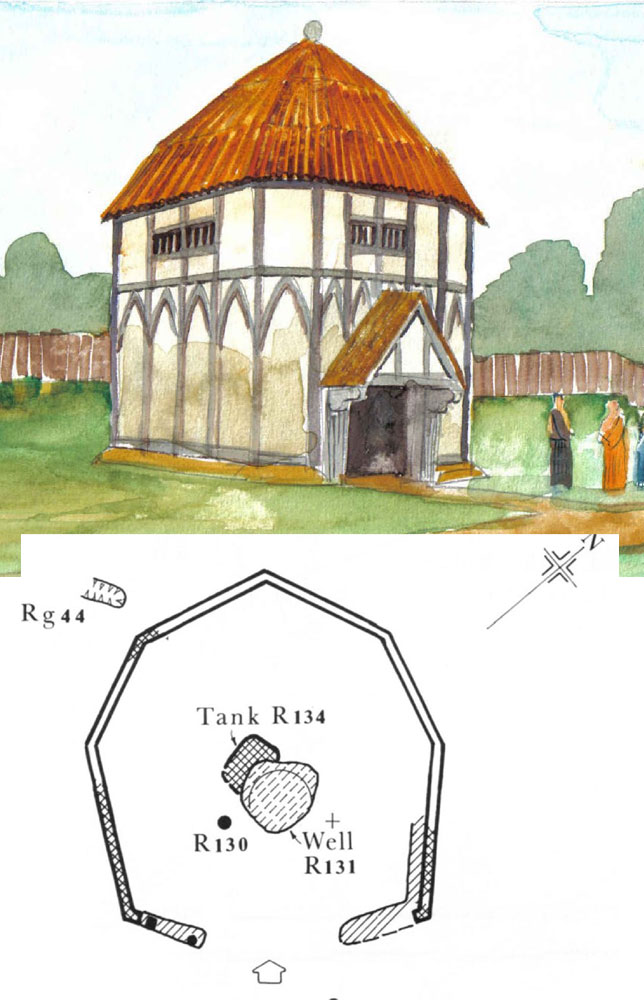

c150AD A major fire hit the town, destroying buildings in its centre and along Ermine Street. Despite this, and episodes of extensive flooding, Godmanchester continued to prosper and grow, and towards the end of the second century, the temple to Abandinus was replaced by a larger temple with a colonnaded walkway around the outside.

Artists Impression

Artists Impression

The prosperity and economy of Godmanchester was primarily based on farming, something that would remain the case for much of the history of Godmanchester. There was no sharp divide between the town and the surrounding farmland for agricultural activity. It took place at the villa found at Rectory Farm and the farmstead at Cardinal Distribution Park, and within the town, buildings have been excavated with threshing floors, drying ovens and wicker granaries.

We know livestock were kept for milk and cheese from the discovery of dairy equipment such as a ridged cheese drainer found in Post Street. Crops such as wheat were grown in an infield and outfield system. The infield was the best land closest to the settlement, farmed and manured intensively, while irregular patches of outfield were farmed less intensively further away from the town. Ridges and furrows were dug by hand, called lazybeds, a system used until modern times in areas of Scotland and Ireland, as was the infield and outfield system.

Close to the mansio complex lay a temple to the god Abandinus. Three successive temples were constructed on the site within a large temenos, or precinct, and both the second and third temple were Romano-British rather than classical in design. The first, constructed in the early second century, was a simple timber-framed rectangular building, while the second, of the late second century, was a box-shrine, also timber-framed, with a veranda held up by timber pillars running around the outside. The second temple was probably destroyed along with the mansio at the end of the third century.

THE THIRD CENTURY AD

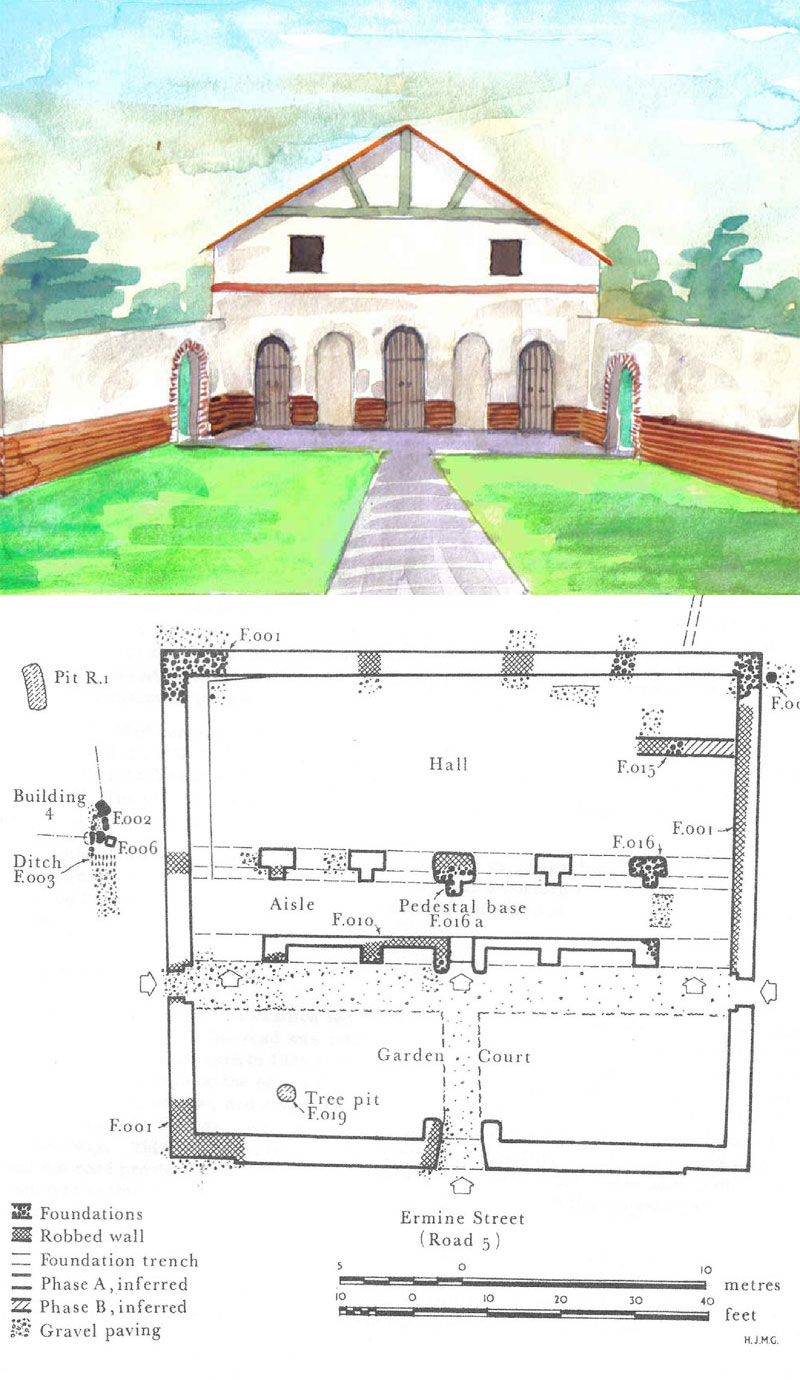

In the early third century the centre of the town was redesigned. A large, official masonry building was constructed, possibly a Roman town hall, or basilica. This may indicate Godmanchester had achieved some degree of self-governance, with an elected local council, and might be associated with Emperor Caracalla's grant of Roman citizenship to all free members of the Empire in 214 AD. Oddly, it was built in front of the line of Ermine Street, so that the road had to be realigned, although this also created an area to the south of the building that became the Roman market square. Artists Impression

Artists Impression

The single-aisled basilica was 24 metres long, 12.9 metres wide, and built of Barnack ragstone and flint masonry, with a roof of tile and Collyweston slate. The upper storey, or clerestory, was carried on arcades. Later, a second aisle wall was added on the west side. At the front on the eastern side was a walled courtyard, from which three entrances led into the hall. Unlike other basilicas, its forecourt was not a forum, and commercial activity focused on the market place Construction of a basilica may have signalled the town had gained self-governing status. However, the building has also been interpreted as principia because of its design. A principia was normally the headquarters of a fort, but some have also been associated with the administration of Imperial Estates, as at Combe Down near Bath. Another possibility is that it was in some way associated with the mansio complex, which was close by. In any of these scenarios, the structure was an impressive, romanised official building.

The redesign created a market square in the centre of the town, with a gravelled pavement and wooden arcade. There, local produce and manufactured goods were sold, alongside imported luxuries like Samian Ware from Gaul and glassware from Egypt. Shops and workshops, such as a bakery and smithy, increased in number.

Small scale industry had developed in Godmanchester, including potteries to the north of the town in the area of the Parks and Park Lane, and a tannery and metal working to the south in the area of St Anne's school. Late 200s AD The town, like others in Britain at the time, began to construct masonry walls, three metres thick, backed by a clay rampart and fronted by a ditch. These walls would never be completed.

c296 AD A hoard of jewellery was buried at the back of the bathhouse. It included a gold necklace and pendant decorated with two human facemasks, an onyx intaglio displaying Ganymedes, gold and silver rings and sixty coins. Whoever buried this jewellery must have intended to come back, but they never returned. Such hoards are thought to be buried at times of threat and conflict. From around the same time bodies have been discovered whose bones were gnawed by dogs or wolves, suggesting they weren't buried. A woman's partially burned body lay in an enclosure ditch. The mansio complex, including the bathhouse and temple, was gutted by fire along with much of the town. Even the villa at Rectory Farm, outside the main settlement, was burned.

Clearly something catastrophic had happened to Roman Godmanchester and its people. We have no written accounts of what happened, but it was probably an attack by Saxon raiders. In 286 AD the usurper Allectus took power in Britain, and in the chaos that ensued Saxon raiders drove further inland. Godmanchester never fully recovered from the disaster.

THE FOURTH CENTURY AD

In areas like the Parks, extensive cemeteries for burials replaced industrial activity and settlement. This seems to show the population had pulled back to live inside the town walls after the third century attack. For the first few centuries of Roman rule, most burials had taken the form of cremations. An example from the mid-second century was found in Oakleigh Crescent by Mr Gerald Reeve. The beautiful Samian ware urn belonged to a young girl, around eight years of age, buried with pipe clay models of a horse and a bull, probably votive offerings. Because she was a child, she was buried within the settlement, rather than was normally the case, in roadside cemeteries outside of the town. But by the fourth century, burials rather than cremations became almost universal in Godmanchester. The shift to burials may have had a practical reason, such as pressure on fuel for funeral pyres.

But it may also signal the arrival of Christianity, as the graves tend to lie east-west with the head to the west. This and the choice of burial over cremation were Christian customs. Constantine the Great converted to Christianity, and we know the religion had reached Britain by the early fourth century as British Bishops attended the Council of Arles in 314 A.D. Godmanchester's position on Ermine Street was well placed for new influences from the Empire, and we know Christianity reached the region through the remarkable discovery of a hoard of liturgical plate at the nearby Roman settlement at Water Newton, the earliest such find in the whole of the Roman Empire.

The remains of Godmanchester's inhabitants tell us a great deal about them. Occasionally, grave goods are discovered, such as a clay ball buried with a girl at what is now Old Court Hall. It was perhaps a favourite toy. Malformations of bone from hard physical labour and dietary deficiency, as well as physical trauma from childbirth and signs of disease like leprosy show that the inhabitants of the town often led hard lives.

Fewer buildings were constructed in the fourth century, although the northern end of the baths was still in use, and a new temple to Abandinus was built. But in the late fourth century, what remained of the public buildings was robbed out to use in defences on the eastern side of the town. On the western side, the gap in the masonry wall defence was filled with earthworks. A new ditch was cut, and towers for defensive artillery added. By the end of the century, traffic had declined hugely on Ermine Street, and the last metalled surface was found to be almost unworn when it was excavated. Godmanchester's existence as part of the Roman Empire was drawing to an end.

THE FIFTH CENTURY AD

411 AD The Emperor Honorius sent a letter to Britain – the people would have to defend themselves against increasing attacks from raiders. Some community leaders hired Saxon mercenaries for defence, and from finds of early Saxon pottery in Godmanchester, this may have happened here. But the lack of distinctively Saxon graves suggests the town may have remained, for a while, Romano-British in character. But Godmanchester was no longer part of the Empire, Britain was to be ruled by Kings, and it seems likely that Godmanchester became a settlement of homesteads, a similar pattern of living found by the Romans when they first arrived.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Porch Museum would like to thank the people listed for their generous contributions and help with the museums display on Roman Godmanchester and from which this article has been taken.

H J M Green

Bob Burn-Murdoc

And artist Alex Williams